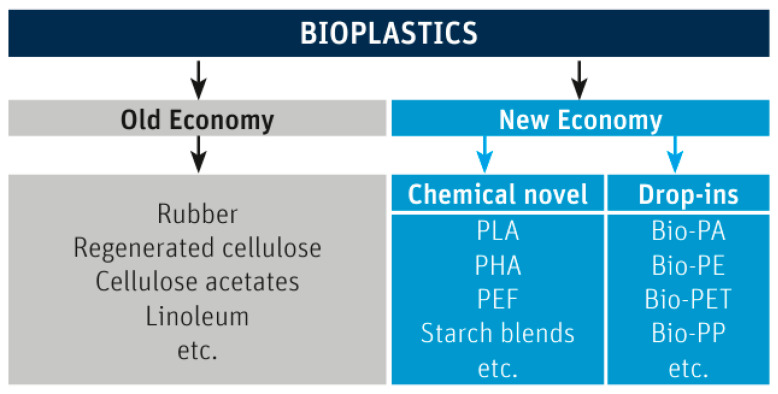

Although bioplastics are not all biodegradable and require specific conditions to degrade, they are increasingly considered ideal alternatives to fossil-based and other non-renewable plastics.

Global bioplastic production is predicted to increase by almost 200%, from around 2.2 million tonnes in 2022 to approximately 6.3 million tonnes in 2027. Other research shows that bioplastic has an anticipated market growth of 20–25 % per year.

This growth is proof that bioplastics are technically viable and commercially established, but does not mean that bioplastics can be scaled to replace fossil-based plastics in full.

A roadmap for decarbonisation suggests substituting 41% of petroleum-based plastics with bio-based alternatives by 2030. This level of replacement is considered feasible from a resource perspective without competing with food production.

This article will explore how much plastic bioplastics can realistically replace and under what conditions bioplastics can be used.

Why Are Bioplastics Seen as a Substitute (Out of All That Plastic)?

Many types of bioplastics are designed to have similar characteristics and functionalities to conventional plastics, enabling easier integration into existing manufacturing, design, and product systems. This way, industries can adopt them within the current plastics economy.

Bioplastics allow companies to diversify away from fossil feedstocks and are sometimes viewed as a supply-chain strategy in volatile fossil markets. This also meets rising consumer demand for sustainable products. A PwC survey of more than 20,000 consumers across 31 countries shows that 80% are willing to pay more for sustainably produced or sourced goods.

Government policies have been instrumental in boosting bioplastic usage as well. For example, India’s single-use plastic ban helped raise bioplastic imports into the country in 2023. The setting and growth of sustainability goals has driven industries to adopt bioplastics to reduce their carbon footprints.

But as we already know, the main strength of bioplastics lies in their environmental advantages. They have the potential to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by at least 30% if not more. Bioplastic production also consumes 65% less energy compared to traditional petroleum-based plastics.

How Much Fossil Plastic Can Bioplastics Realistically Replace?

Based on mechanical performance characteristics alone, bio-based plastics are technically capable of replacing up to 90% of the global petroleum-based plastics market. But this number does not reflect real-world limits on biomass, land use, and end-of-life systems.

While the technical potential for replacement is high, the current market share of bio-based plastics is only 1%, and scaling this up involves specific targets and resource constraints.

In the roadmap exploring plastics decarbonisation, researchers modelled how much petroleum-based plastic could be replaced based on biomass feedstock availability. Results indicated that around 41% substitution could be feasible by 2030 using agricultural residues alone, including corn stover and wheat straw, without directly competing with food production.

Extending this resource mobilisation, the model suggests that bio-based plastics could technically reach 80% market share by 2040 and up to 90% by 2050, representing the upper limit of substitution under highly optimistic feedstock supply conditions.

What Sets the Substitution Limit?

Based on the available research, a complete transition to bioplastics is not currently achievable. In practice, the constraint is not whether plastics can be made from biomass, but whether they can be produced at scale, sustainably, and within existing industrial systems. Below are the key factors that set this limit.

1. Land-Use and Environmental Trade-Offs

Scaling bioplastics to meet global demand would place substantial pressure on land systems, potentially creating new environmental harms.

2. Technical Gaps in Polymer Substitution

There remains a structural “hard cap” on replacement because certain polymers still lack commercially viable bio-based equivalents. Plastics such as polystyrene (PS), polycarbonate (PC), and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) do not yet have fully bio-based versions at commercial scale.

Global decarbonisation modelling suggests that large-scale substitution with bio-based plastics could drive approximately 20% more deforestation, 22% more cropland expansion, and 35% greater agricultural intensification by 2040 compared with baseline scenarios.

Many commercially available bioplastics still rely on first-generation feedstocks (e.g., corn, sugarcane). Although second-generation feedstocks such as residues and waste are developing, they remain technologically less mature and harder to scale.

3. Physical Resource Scarcity

Even where land is theoretically available, specific biomass inputs are insufficient to support full replacement. For example, replacing polypropylene (PP) with bio-PP at a level consistent with 90% bio-based plastics by 2050 would require approximately 174 times the current global supply of used vegetable oil, far beyond realistic availability.

Certain bioplastics, such as PHB (polyhydroxybutyrate) produced from biogas, are highly energy-intensive. Without a fully renewable energy system, these processes do not necessarily deliver lower life-cycle emissions than fossil-based plastics.

4. Infrastructure and Waste-System Constraints

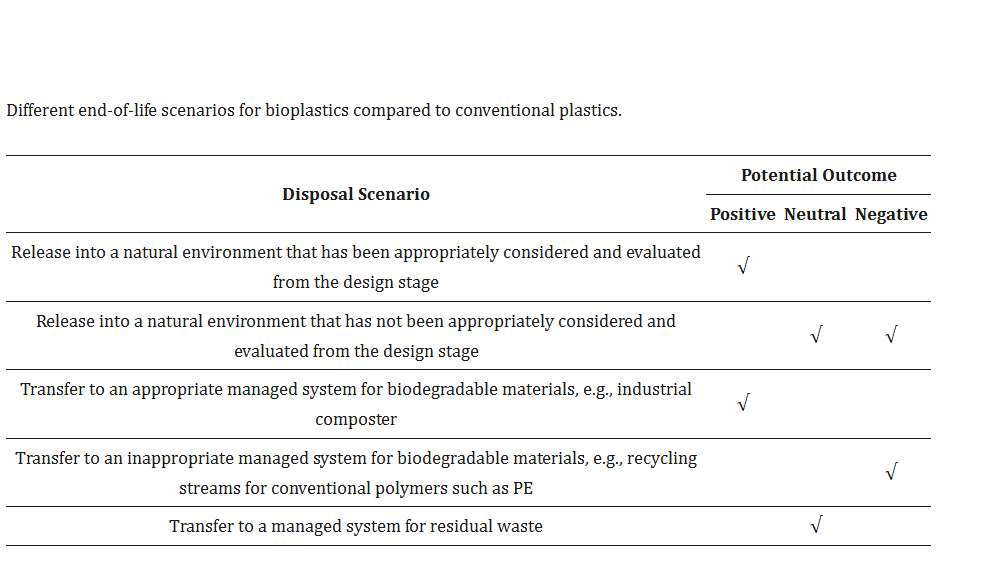

Today’s waste-management systems are not designed to handle a large influx of bioplastics. Many biodegradable plastics require industrial composting facilities and will not degrade in natural environments. These facilities remain scarce, and consumer confusion often leads to mis-disposal.

Biodegradable and bio-based plastics can contaminate conventional recycling streams, and most facilities lack the technology to reliably separate them.

5. Economic and Policy Lock-In

Many plastic feedstocks are co-produced with fuels, making them cheap and structurally advantaged. Meanwhile, bio-based alternatives remain less competitive without policy support, such as carbon pricing, mandates for bio-based content, or restrictions on fossil feedstocks.

When Does It Make Sense to Replace Plastic with Bioplastics?

Based on the available evidence, there is strong guidance on when it is both strategic and environmentally sound to replace conventional fossil-based plastics with bioplastics.

1. When Products Are Likely to Be Lost to the Environment

With the proper waste management system, biodegradable plastics are well suited for products that are frequently littered or irretrievable, such as fruit and vegetable stickers, tea bags, and certain fireworks components.

In applications where material abrasion is unavoidable, such as car tires, shoe soles, and geotextiles, biodegradable materials can reduce the long-term persistence of microplastic particles in ecosystems.

2. When Products Have a Short Service Life (Single-Use)

Small or contaminated items (e.g., candy wrappers or single-portion snack packaging) are often unsuitable for mechanical recycling. Compostable or biodegradable alternatives can be more appropriate where proper waste treatment exists.

This also applies to agricultural products. Products such as mulch films benefit from being biodegradable because they can be ploughed into soil after harvest, avoiding the costly retrieval and disposal of heavily soiled plastic waste.

3. When a Controlled Lifespan Is Required

Bioplastics are especially valuable when a product needs a predetermined functional lifetime. Through specific polymer design or enzyme-based additives, materials can be tailored to last only as long as required for example, a tree clip that provides support for three years before safely disintegrating. This avoids long-term accumulation of unnecessary material.

Rethinking Plastic Substitution

Replacing one material with another does not solve the deeper issues of overproduction, weak waste systems, and the massive volume of plastic already polluting our oceans. Substitution, when done alone, risks shifting environmental burdens rather than eliminating them.

This is why the most impactful strategy does not start with what material we use next, but with what we can avoid, recover, and redesign today.

At Seven Clean Seas, we focus on tackling the plastic crisis at its source, by removing plastic waste from coastlines, rivers, and oceans before it can fragment into microplastics or enter the food chain.

Through verified recovery, transparent data, and community-based cleanup operations, we address the legacy plastic already harming marine ecosystems while helping brands and organisations take responsibility for the plastic they cannot yet eliminate.

If we want a future with less plastic in our oceans, the solution is not simply switching materials, but rethinking the entire system. Reduce what you can, replace only where it truly makes sense, and take responsibility for the plastic that already exists by helping remove it from the environment starting today.

Want to explore more about our work? Send us a message at hello@sevencleanseas.com!